What's ape

focusThe genus Homo, to which all human beings belong, is believed to have evolved from Australopithecus around 2–3 million years ago. Lucy, the Australopithecus afarensis ape, whose skeleton was pieced together from several hundred pieces of bone fossils, is the best known example of this genus. A gene duplication event that happened around 3.4 million years ago might have provided Lucy and her descendants with a boost to their brainpower.

Figure 1. Australopithecus afarensis. Reconstruction of “Lucy”, Warsaw Museum of Evolution. Created by Shalom, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1. Australopithecus afarensis. Reconstruction of “Lucy”, Warsaw Museum of Evolution. Created by Shalom, Wikimedia Commons.

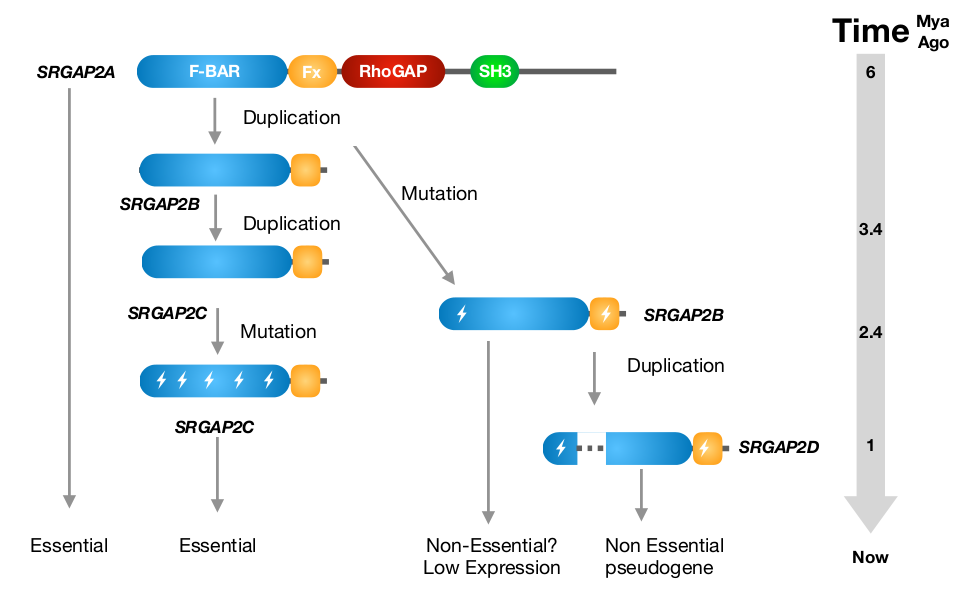

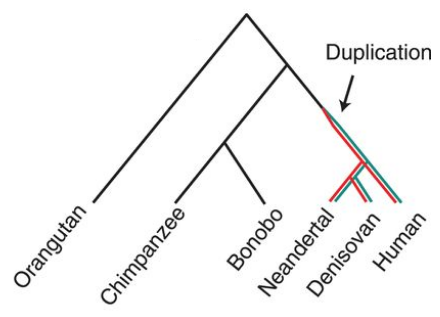

This duplicated gene is known as SRGAP2 (Slit-Robo RhoGTPase-activating protein 2) [1]. The ancestral SRGAP2A protein (often referred to as SRGAP2) is a RhoGTPase regulator involved in neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth [2]. The gene duplication created a truncated paralogue, SRGAP2B, which was itself duplicated around 1 million years later (~2.4 million years ago) to create a ‘granddaughter’ paralogue, known as SRGAP2C (Figure 2). This paralogue is believed to be important for the expansion of the neocortex when the transition from Australopithecus to Homo took place [3].

Figure 2. Evolutionary history of SRGAP2 proteins. Modified figure from Sporny et al., Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017 [6].

Figure 2. Evolutionary history of SRGAP2 proteins. Modified figure from Sporny et al., Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017 [6].

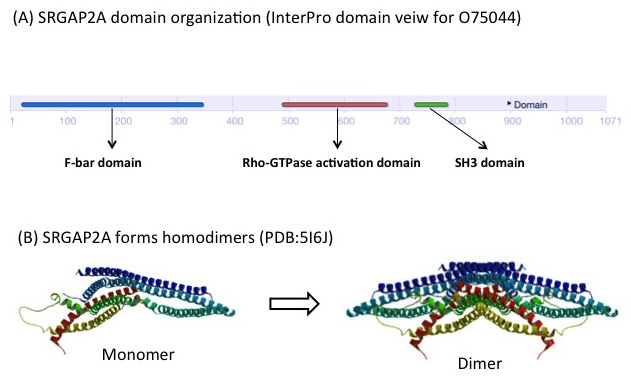

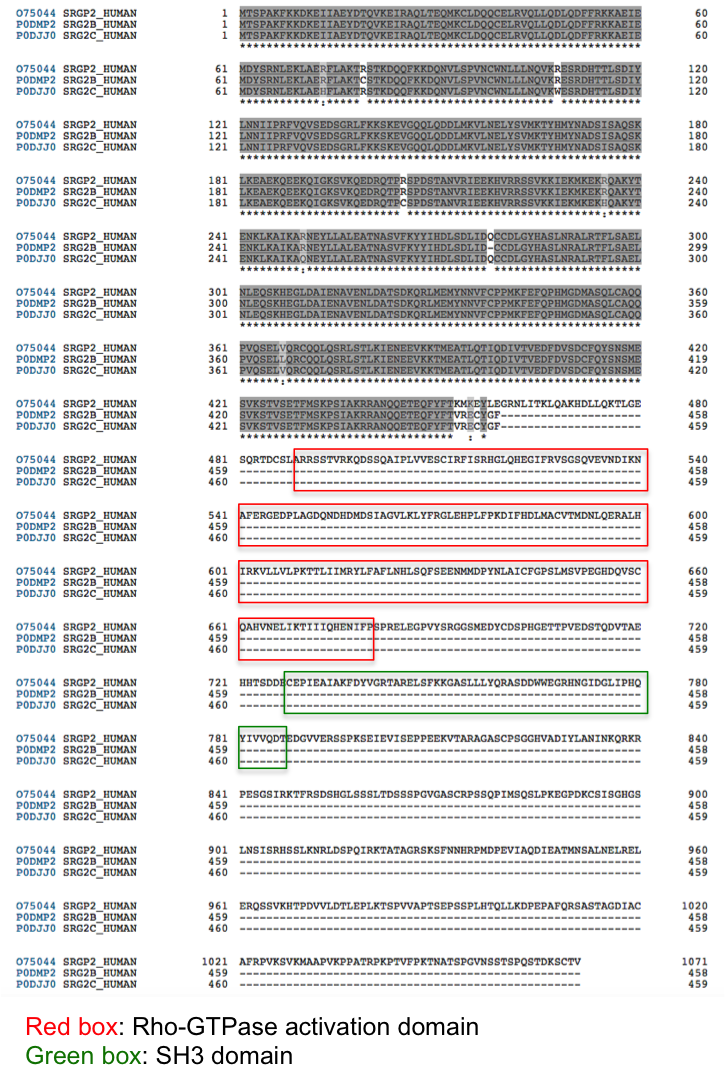

SRGAP2A contains a F-BAR, a RhoGAP and a SH3 domain. It forms homodimers through its F-BAR domain (Figure 3), which promotes spine maturation and limits spine density in the neocortex [4]. SRGAP2C lacks the RhoGAP and the SH3 domain, but retains part of the F-BAR domain. The F-BAR domain of SRGAP2C can form heterodimers with SRGAP2A. This prevents SRGAP2A from forming homodimers, and consequently inhibits its function. From a study conducted in mice, it appears that expression of SFGAP2C causes sustained radial migration in the neocortex and leads to the emergence of human-specific features, including neoteny (delaying of development) during spine maturation and increased density of longer spines [4]. The antagonism of SRGAP2A by SRGAP2C may therefore play an important role during human brain development [3].

Figure 3. SRGAP2A forms dimers through its F-BAR domain. (A) Domain organisation of SRGAP2A in InterPro (B) Structure of SRGAP2A monomer and dimer (PDB:5I6J) [6].

Figure 3. SRGAP2A forms dimers through its F-BAR domain. (A) Domain organisation of SRGAP2A in InterPro (B) Structure of SRGAP2A monomer and dimer (PDB:5I6J) [6].

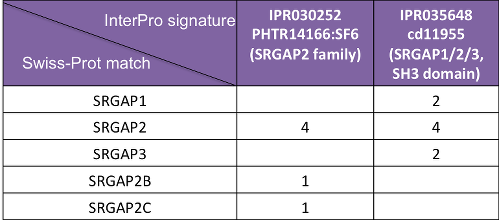

In InterPro, SRGAP2A proteins are matched by both the SRGAP2 family (IPR030252) and the SRGAP1/2/3, SH3 domain (IPR035648) entries. However, SRGAP2B and SRGAP2C proteins are only matched by the SRGAP2 family entry (Figure 4), as SRGAP2A/B/C share similarity at their N terminus (Figure 5), but SRGAP2B/C lack the SH3 domain.

Figure 4. SRGAP2 homologues in InterPro. Numbers indicate the Swiss-Prot protein match.

Figure 4. SRGAP2 homologues in InterPro. Numbers indicate the Swiss-Prot protein match.

Figure 5. Alignment of SRGAP2A/2B/2C.

Figure 5. Alignment of SRGAP2A/2B/2C.

In evolution, gene duplication is an important mechanism for generating novel functionality in organisms [5]. So it is no surprise that SRGAP2 is not the only case where gene duplication has created a new functional gene that has had a great impact on evolution. Another example is the ARHGAP11B gene that arose from the partial duplication of ARHGAP11A after the hominin lineage split from genus Pan (Figure 6). ARHGAP11B has also been linked to the expansion of the human neocortex [3].

Figure 6. Phylogenetic tree showing duplication of ARHGAP11B (red) from ARHGAP11A (green). Florio et al., Science. 2015. [8].

Figure 6. Phylogenetic tree showing duplication of ARHGAP11B (red) from ARHGAP11A (green). Florio et al., Science. 2015. [8].

Due to their high sequence identity, many human gene duplications are difficult to disentangle during genome assembly and hence are still unverified. Nevertheless, there might be more genes like SRGAP2C and ARHGAP11B in the human genome to be discovered. For InterPro, these newly identified paralogues will complicate how we annotate protein family functions and assign GO (Gene Ontology) terms, as truncated proteins may have different (or even inhibitory) effects to full length family members. Regular reviews and updates of our database/entries will be the key to annotation of these paralogues.

-

Dennis MY, Nuttle X, Sudmant PH, Antonacci F, Graves TA, Nefedov M, Rosenfeld JA, Sajjadian S, Malig M, Kotkiewicz H, Curry CJ, Shafer S, Shaffer LG, de Jong PJ, Wilson RK, Eichler EE. Evolution of human-specific neural SRGAP2 genes by incomplete segmental duplication. Cell. 11;149(4):912-22. 2012. [PMID: 22559943]

-

Yue Ma, Ya-Jing Mi, Yun-Kai Dai, Hua-Lin Fu, Da-Xiang Cui, Wei-Lin Jin1. The Inverse F-BAR Domain Protein srGAP2 Acts through srGAP3 to Modulate Neuronal Differentiation and Neurite Outgrowth of Mouse Neuroblastoma Cells. PLoS One. 8(3):e57865. 2013. [PMID: 23505444]

-

Hillert DG. On the Evolving Biology of Language. Front Psychol. 24;6:1796. 2015. [PMID: 26635694]

-

Charrier C, Joshi K, Coutinho-Budd J, Kim JE, Lambert N, de Marchena J, Jin WL, Vanderhaeghen P, Ghosh A, Sassa T, Polleux F. Inhibition of SRGAP2 function by its human-specific paralogs induces neoteny during spine maturation. Cell. 149(4):923-35. 2012. [PMID: 22559944]

-

Magadum S, Banerjee U, Murugan P, Gangapur D, Ravikesavan R. J Genet. Gene duplication as a major force in evolution. 92(1):155-61. 2013. [PMID: 23640422]

-

Sporny M, Guez-Haddad J, Kreusch A, Shakartzi S, Neznansky A, Cross A, Isupov MN, Qualmann B, Kessels MM, Opatowsky Y. Structural History of Human SRGAP2 Proteins. Mol Biol Evol. 1;34(6):1463-1478. 2017.[PMID: 28333212]

-

Dennis MY, Eichler EE. Human adaptation and evolution by segmental duplication. Curr Opin Genet Dev.41:44-52. 2016. [PMID: 27584858]

-

Florio M, Albert M, Taverna E, Namba T, Brandl H, Lewitus E, Haffner C, Sykes A, Wong FK, Peters J, Guhr E, Klemroth S, Prüfer K, Kelso J, Naumann R, Nüsslein I, Dahl A, Lachmann R, Pääbo S, Huttner WB. Human-specific gene ARHGAP11B promotes basal progenitor amplification and neocortex expansion. Science. 24;6:1796. 2015. [PMID: 25721503]