Interpro and rare diseases, an interesting example

focusThe 28th of February, the 29th in leap years, is the day to raise awareness of the over 5,000 rare diseases that affect millions of people worldwide [1, 2]. Although research on these disorders has increased over the last decades, there are still great challenges to overcome.

One of these disorders is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a rare fatal progressive neurodegenerative disease characterised by the death of motor neurons that eventually leads to paralysis and respiratory failure within a median of 2-5 years. The proteins most commonly affected in ALS include TDP-43, SOD1, FUS and the C9orf72 protein [3]. Besides its etiologic role in the disease, TDP-43 is currently being studied for the development of a precise biomarker for ALS [4].

TDP-43 is a DNA/RNA-binding protein, which, when binding to DNA is able to prevent gene transcription, while when binding to RNA, it is involved in many RNA processes, namely mRNA transcription, splicing and stability, being essential for ribonucleoprotein particle (hnRNP) interactions and splicing activity. Therefore, it plays regulatory roles in diverse events, such as embryogenesis, central nervous system function and fat metabolism. Additionally, although TDP-43 is predominantly localised in the nucleus, it also shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm where it plays a role in granule assembly [6, 7].

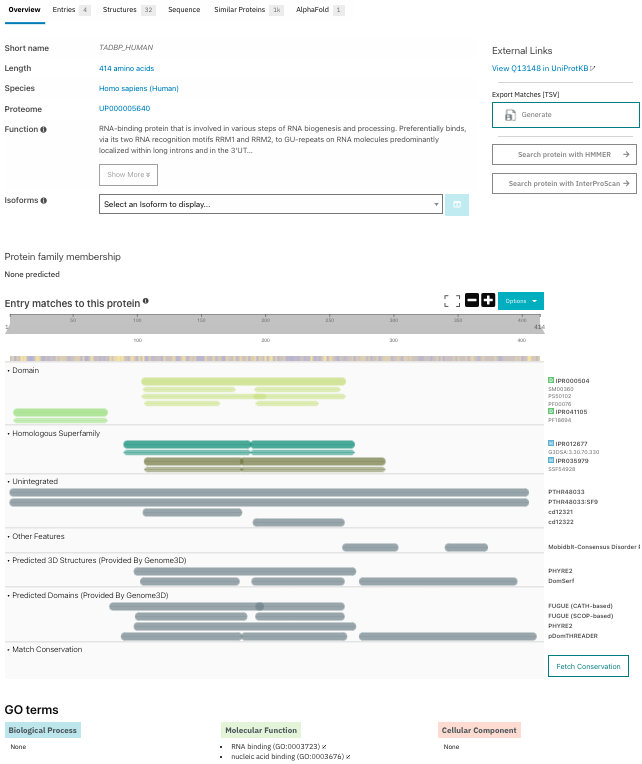

TDP-43 is a multidomain protein, consisting of an N-terminal domain which includes a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), two RNA recognition motifs (RRM1/2) and a glycine-rich intrinsically disordered C-terminal domain [5, 6, 8]. Figure 1 shows the different domains for human TDP-43 Q13148 in InterPro.

Figure 1. InterPro provides an accessible summary on the current knowledge of the protein, with curated functional annotations and automatic predictions, such as the C-terminal disordered regions. Links to the InterPro entry pages: TDP-43 N-terminal IPR041105 and RRM IPR000504 domains, RNA-binding domain superfamily IPR035979, Nucleotide-binding alpha-beta plait domain superfamily IPR012677 and to UniProt are available as well as downloadable options.

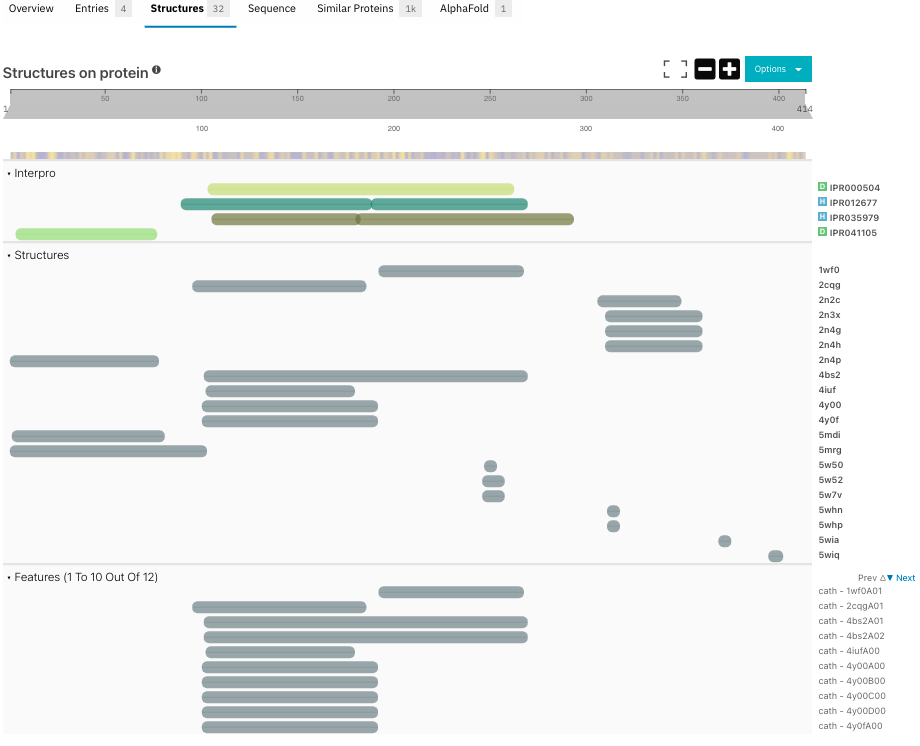

A remarkable neuropathological hallmark of ALS is the presence of cytoplasmic protein aggregates of which TDP-43 is a major component, that contribute to motor neurodegeneration [5, 6]. Interestingly, these aggregates have been detected in nearly 97% of ALS patients, although mutations in the gene coding for TDP-43 are seen in less than 5% of ALS cases [9]. Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and cleavage of C-terminal fragments exacerbate its aggregation [6]. The C-terminal domain shows low sequence complexity similar to a prion-like domain, a key factor for the protein-protein interactions on TCP-43 [9, 10]. Although the purification of TDP-43 has been possible [11], the structure of the entire protein has not been experimentally resolved yet, as shown in Figure 2. This is due to the low complexity nature of the C-terminal region. Structural studies have reported that the C-terminal domain is responsible for aggregation, although the other domains also contribute to this event [6].

Figure 2. Experimental structures corresponding to each domain of TDP-43 are displayed in the Structures tab of the InterPro protein page.

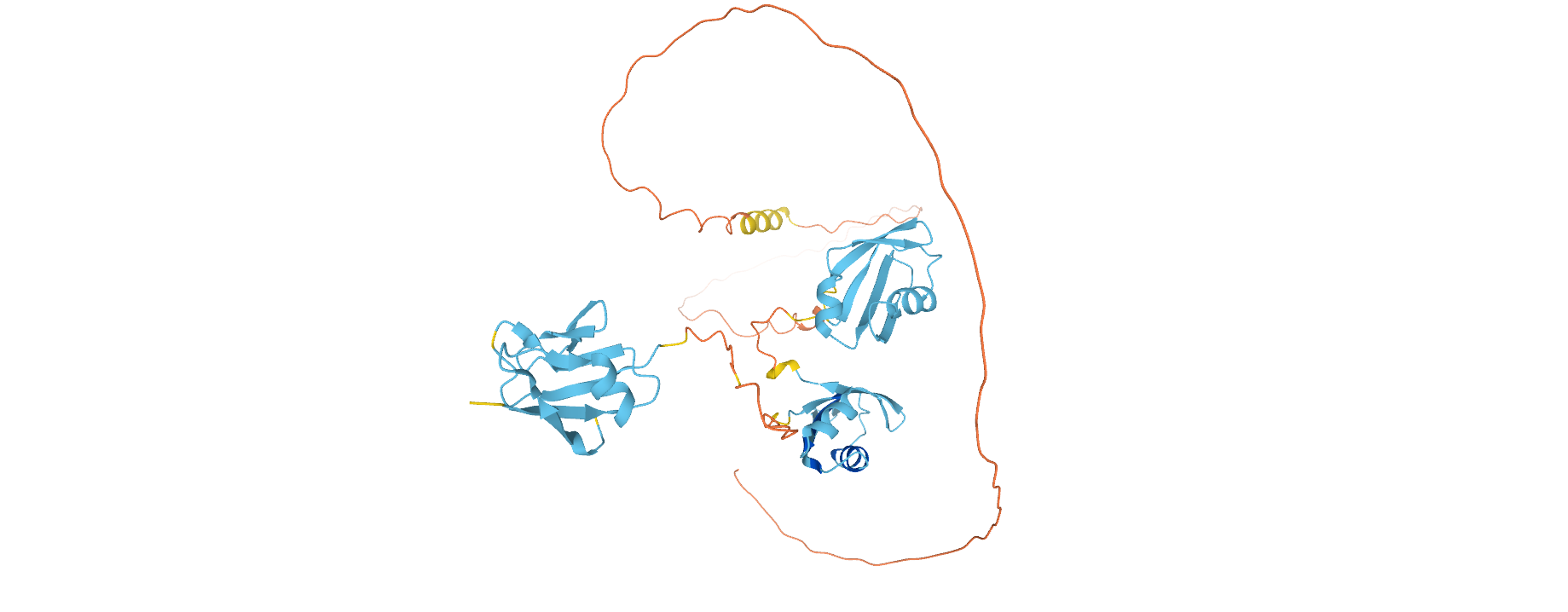

When available, an AlphaFold tab, which includes structure predictions based on full-length protein sequences developed by AlphaFold DB [12] allows the visualisation of all domains and disordered/low complexity regions of TDP-43 (Figure 3) and facilitates the analysis of domain interactions and space arrangement when experimental structures are not available.

Figure 3. Structure prediction of Q13148 from AlphaFold, an overview of the full length protein.

It has been shown that the aggregation of this protein within motor nerves occurs before axonal degeneration, therefore, it may constitute an interesting and useful marker for earlier diagnosis of ALS, which is essential for the efficacy of any treatment [13]. InterPro integrates information from several databases and is regularly updated, which represents an important tool to assist researchers in the development of, not only novel therapies, but also diagnosis techniques for earlier detection of this kind of illnesses. Both are key to improving the quality of life of the affected people.

References:

- https://www.rarediseaseday.org/what-is-rare-disease-day/

- Richter T et al. Rare Disease Terminology and Definitions-A Systematic Global Review: Report of the ISPOR Rare Disease Special Interest Group. Value in Health. 2015, Aug 18. 18(6):906-914 DOI: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.05.008 (PMID: 26409619).

- Hulisz D. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: disease state overview. The American Journal of Managed Care, 01 Aug 2018, 24(15 Suppl):S320-S326 (PMID: 30207670).

- Feneberg E et al. Towards a TDP-43-Based Biomarker for ALS and FTLD. Molecular Neurobiology, 19 Feb 2018, 55(10):7789-7801. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0947-6. (PMID: 29460270).

- Oberstadt M et al. TDP-43 self-interaction is modulated by redox-active compounds Auranofin, Chelerythrine and Riluzole. Scientific Reports, 02 Feb 2018, 8(1):2248 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20565-0 (PMID: 29396541).

- Rao PPN et al. Strategies in the design and development of (TAR) DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) binding ligands. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 08 Aug 2021, 225:113753 DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113753 (PMID: 34388383).

- Budini et al. Cellular model of TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) aggregation based on its C-terminal Gln/Asn-rich region. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 10 Jan 2012, 287(10):7512-7525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m111.288720 (PMID: 22235134).

- Floare ML et al. Why TDP-43? Why Not? Mechanisms of Metabolic Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neuroscience Insights, 17 Sep 2020, 15:2633105520957302. doi: 10.1177/2633105520957302 (PMID: 32995749).

- Versluys L et al. Expanding the TDP-43 Proteinopathy Pathway From Neurons to Muscle: Physiological and Pathophysiological Functions. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 03 Feb 2022, 16:815765. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.815765 (PMID: 35185458).

- Prasad A et al. Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019 Feb 14;12:25. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00025. (PMID: 30837838)

- Vivoli Vega M et al. Isolation and characterization of soluble human full-length TDP-43 associated with neurodegeneration. FASEB J. 2019 Oct;33(10):10780-10793. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900474R. Epub 2019 Jul 9. (PMID: 31287959).

- Jumper J et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021 Jul 15;1-7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 (PMID: 34265844).

- Riva N et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 aggregates in peripheral motor nerves of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2022 Jan 25. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab285 (PMID: 35076694).