Does Taste Depend On Genetics

focusEating is both necessary and potentially dangerous due to the risk of ingesting harmful substances (toxins, bacteria, parasites). Our senses of taste and smell have evolved to help us detect and avoid these dangers, especially through aversion to bitter (often poisonous) and sour (often spoiled) tastes and smells. Not everyone perceives or prefers foods the same way. Genetics play a significant role in how individuals detect and enjoy (or dislike) certain tastes, such as bitterness, sweetness, fat, and the smell of spoiled foods. This genetic diversity affects both food intake and preferences. Human taste and smell have been shaped by evolutionary pressures in different environments. Some animals have lost certain taste abilities (e.g., cats can’t taste sweet) due to their specialised diets, while humans remain generally able to eat a wide range of foods [1].

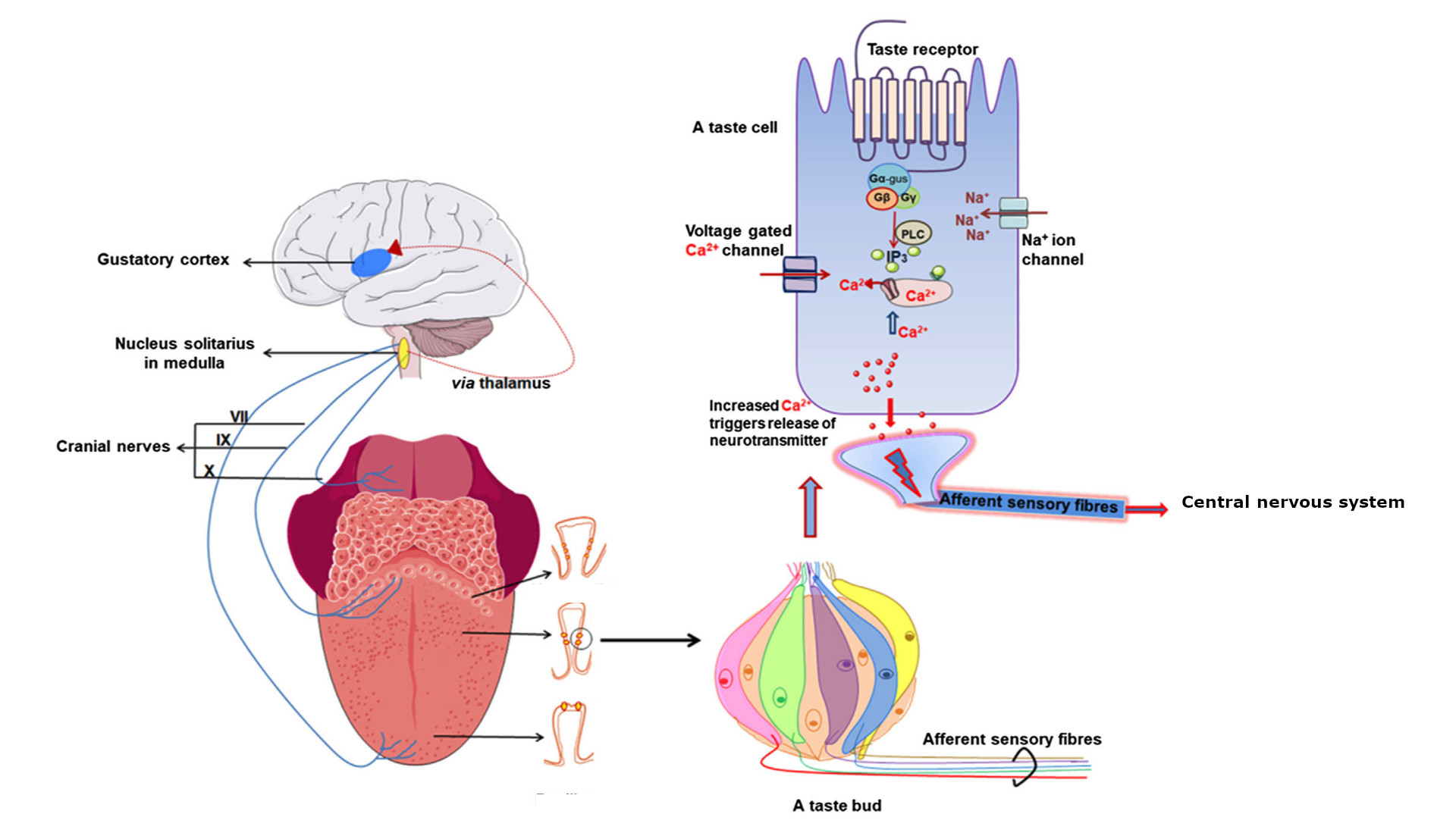

Taste receptors are specialised proteins located primarily on the tongue that detect and respond to chemical compounds in food, enabling the sensation of taste. These receptors are found within taste buds, which are clustered in structures called papillae on the tongue, as well as in other areas such as the palate, throat, and even parts of the digestive system [2, 3].

There are five basic tastes that human taste receptors can detect, each sensed by different types of receptors:

- Bitter, sweet, and umami tastes are detected by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).

- Salty and sour tastes are sensed by ion channels that respond to specific ions (like sodium for salty, hydrogen for sour).

When a molecule responsible for taste binds to its specific receptor, it triggers a cascade of cellular events [4]. See Figure 1 for a schematic graph of this process.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing taste signal transmission between the tongue (with taste buds that contain taste cells harbouring GPCRs) and brain. Taste GPCRs are activated by specific food compounds, recruit specific G proteins that further induce intracellular calcium release. Adapted from [5].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing taste signal transmission between the tongue (with taste buds that contain taste cells harbouring GPCRs) and brain. Taste GPCRs are activated by specific food compounds, recruit specific G proteins that further induce intracellular calcium release. Adapted from [5].

An example, bitter taste

Plants, while abundant and nutritious, have developed an array of chemical defences (toxins) to deter herbivores. Nearly all plant species produce such compounds, some of which are highly toxic (e.g., alkaloids in hemlock, cardiac glycosides in oleander).

Herbivores, including humans, have evolved strategies to circumvent these defences, with bitter taste perception being a particularly effective adaptation. This sensory system enables animals to detect potential toxins before ingestion, thus reducing the risk of poisoning.

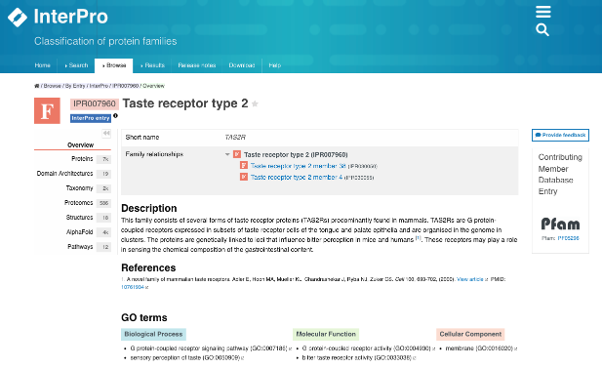

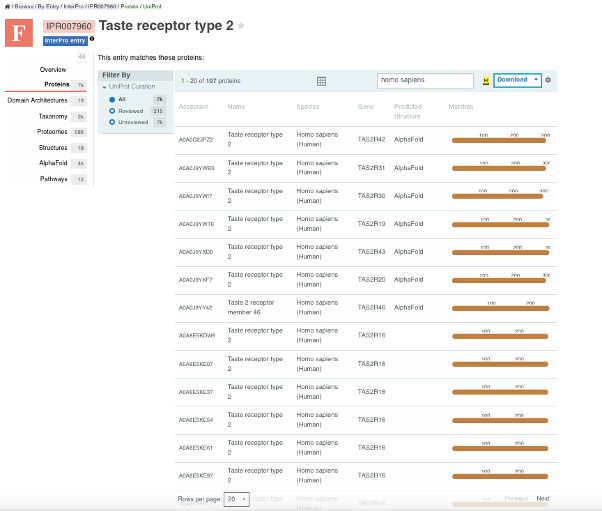

This ability is mediated by a family of GPCRs known as TAS2Rs (see Figure 2) [6]. In the InterPro page for this family, the list of TAS2R protein sequences available in UniprotKB can be easily displayed (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. InterPro page for the Taste receptor type 2 (TAS2R) protein family (IPR007960).

Figure 2. InterPro page for the Taste receptor type 2 (TAS2R) protein family (IPR007960).

Figure 3. InterPro page with a list of the human sequences in UniProtKB that belong to this protein family.

Figure 3. InterPro page with a list of the human sequences in UniProtKB that belong to this protein family.

These proteins are related to other GPCRs involved in environmental sensing, including olfactory receptors (ORs) and opsins (RHO and OPNs), which operate through similar molecular mechanisms [7].

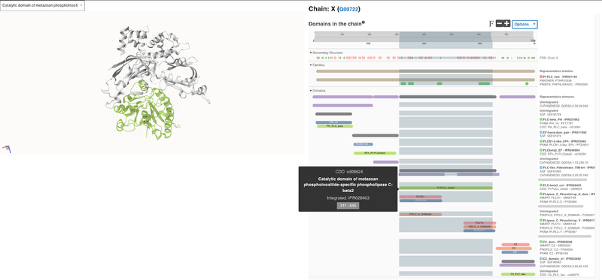

When stimulated by bitter compounds, TAS2Rs activate a transduction cascade involving Phospholipase C Beta 2 (PLCB2, see Figure 4), Calcium homeostasis modulator protein 1 (CALHM1, see Figure 5), and other signalling molecules, ultimately leading to the release of neurotransmitters and the perception of bitterness [6].

Figure 4. Split full-screen view of the crystal structure of human Phospholipase C Beta 2 (PLCB2) with the contributing signature CD16209 for the catalytic domain InterPro entry IPR028403 highlighted in light green. This domain, which shows a TIM barrel fold, contains two regions of homology, sometimes referred to as ‘X-box’ (IPR000909) and ‘Y-box’ (IPR001711), with a variable large loop in between that is commonly referred to as the X-Y linker and is fundamental for the activation of the enzyme [8].

Figure 4. Split full-screen view of the crystal structure of human Phospholipase C Beta 2 (PLCB2) with the contributing signature CD16209 for the catalytic domain InterPro entry IPR028403 highlighted in light green. This domain, which shows a TIM barrel fold, contains two regions of homology, sometimes referred to as ‘X-box’ (IPR000909) and ‘Y-box’ (IPR001711), with a variable large loop in between that is commonly referred to as the X-Y linker and is fundamental for the activation of the enzyme [8].

Figure 5. Split full-screen view of the Cryo-EM structure of octameric human CALHM1 with the contributing signature PTHR32261 for family type InterPro entry IPR029569 highlighted in brown. The coverage of the signature corresponds to one of the monomers or copies that form the homooctamer.

Figure 5. Split full-screen view of the Cryo-EM structure of octameric human CALHM1 with the contributing signature PTHR32261 for family type InterPro entry IPR029569 highlighted in brown. The coverage of the signature corresponds to one of the monomers or copies that form the homooctamer.

TAS2Rs are also expressed in the gut and airways, where they may play roles in endocrine responses, gastric emptying, immune reactions, and even detection of microbial activity. They are considered potential targets to prevent or treat metabolic disorders [9].

Each TAS2R receptor can respond to multiple bitter compounds, and most bitter compounds can activate multiple TAS2Rs. There is significant overlap in the types of compounds that activate TAS2Rs across different species, suggesting evolutionary conservation despite dietary differences.

In addition, there is extensive allelic variation in TAS2R genes among individuals, leading to differences in taste sensitivity and preferences, which in turn shape consumption behaviours and health outcomes [6].

But what about spiciness or pungency? Isn’t it a taste?

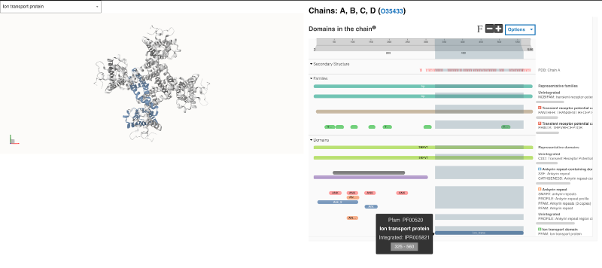

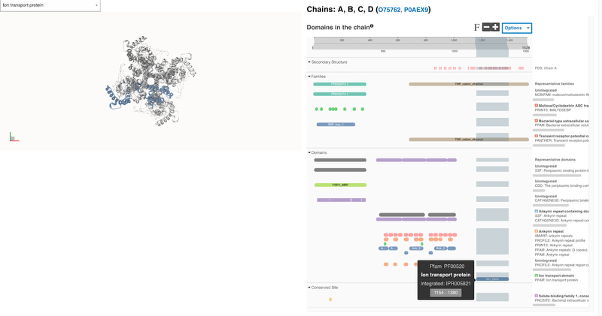

Capsaicin, found in chilli peppers; piperine, found in black pepper; and allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), found in cruciferous vegetables such as mustard, radish, horseradish, and wasabi, are compounds responsible for spicy sensations [10]. These molecules activate pain and temperature receptors (all of them activate the TRPV1 channel, but AITC also activates TRPA1) in the mouth [11, 12]. TRPV1 (transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, Figure 6) and TRPA1 (Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily A member 1, Figure 7) are not taste receptors; they are involved in the detection of thermo-sensation (heat), autonomic thermoregulation, nociception (pain), food intake regulation and multiple functions in the gastrointestinal tract [13, 14]. This activation sends signals to the brain that are interpreted as sensory experience of pain or heat, rather than a taste.

Figure 6. Split full-screen view of the Structure of the rat capsaicin receptor (TRPV1) with the contributing signature PF00520 for the Ion transport domain InterPro entry IPR005821 highlighted in blue. Four copies of the protein form a channel complex [15]. The structure of the human capsaicin receptor has not been solved yet.

Figure 6. Split full-screen view of the Structure of the rat capsaicin receptor (TRPV1) with the contributing signature PF00520 for the Ion transport domain InterPro entry IPR005821 highlighted in blue. Four copies of the protein form a channel complex [15]. The structure of the human capsaicin receptor has not been solved yet.

Figure 7. Split full-screen view of the Structure of the human TRPA1 ion channel with the contributing signature PF00520 for the Ion transport domain InterPro entry IPR005821 highlighted in blue. Four copies of the protein form a channel complex. TRPA1, also known as the Mustard and Wasabi Receptor, can be activated by a variety of structurally diverse pungent natural products, environmental toxic irritants, industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals, as well as endogenous reactive mediators [16].

Figure 7. Split full-screen view of the Structure of the human TRPA1 ion channel with the contributing signature PF00520 for the Ion transport domain InterPro entry IPR005821 highlighted in blue. Four copies of the protein form a channel complex. TRPA1, also known as the Mustard and Wasabi Receptor, can be activated by a variety of structurally diverse pungent natural products, environmental toxic irritants, industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals, as well as endogenous reactive mediators [16].

For this reason, responses triggered by pungent molecules are important for the study of pain modulation but also in other pathological conditions such as obesity, airway diseases, and urological disorders [13,14].

Production of capsaicin and related molecules by plants might be advantageous for seed dispersal, as their seeds are dispersed predominantly by birds, whose TRPV1 channel does not respond to capsaicin or related chemicals, while mammalian TRPV1 is very sensitive to it. This is advantageous to the plant, as chilli pepper seeds consumed by birds pass through the digestive tract and can germinate later, whereas mammals have molar teeth that destroy such seeds and prevent them from germinating [17, 18]. There is also evidence that capsaicin is a natural antifungal [19].

But then, why do people like spiciness?

As an example, capsaicin repels almost all mammals, with rare exceptions like the tree shrew [20]. However, humans are the only animals known to willingly eat foods that cause irritation, discomfort, and even pain. Several theories may explain this human behaviour:

- The endorphin and dopamine rush

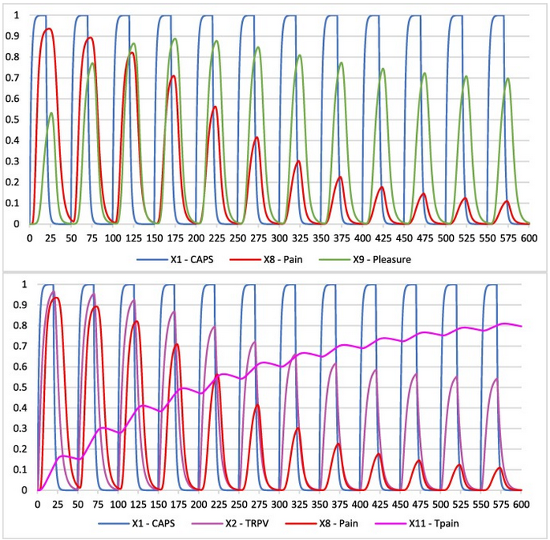

In response to the sensation of pain triggered by the ingestion of capsaicin, your brain releases endorphins (natural painkillers) and dopamine (a reward neurotransmitter), which ultimately can lead to shifting your experience from negative (pain) to positive (pleasure) [21, 22]. A recent study employed an adaptive causal network model to outline the processes related to capsaicin consumption (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Upper graph: Simulation of pain and pleasure perception, induced by capsaicin. Over time the perception of pleasure becomes dominant over the pain perception. Lower graph: Simulation of TRPV1 activity, pain perception, and threshold for pain. The perception of pain decreases over time as a result of an increasing threshold for pain and hence less activity of the TRPV1 receptor [21].

Figure 8. Upper graph: Simulation of pain and pleasure perception, induced by capsaicin. Over time the perception of pleasure becomes dominant over the pain perception. Lower graph: Simulation of TRPV1 activity, pain perception, and threshold for pain. The perception of pain decreases over time as a result of an increasing threshold for pain and hence less activity of the TRPV1 receptor [21].

- ‘Benign masochism’, sensation seeking and reward sensitivity

The “benign masochism” theory suggests people enjoy negative or threatening experiences—like the pain from spicy food—when they know they’re actually safe. Besides, sensation seeking and sensitivity to reward are personality traits that drive individuals to pursue intense or novel experiences, and spicy food offers a safe way to experience a controlled “thrill” or challenge [23, 24].

- Cultural factors, adaptation and exposure

Repeated exposure to spicy foods, especially from a young age, can increase tolerance and preference. Cultural traditions and family habits strongly influence spicy food consumption [25].

- Potential benefits

Additionally, there are health benefits to pungent compounds such as capsaicin that are supported by research [26], but individual responses vary, and people with certain digestive conditions may need to moderate their intake.

And coriander? Why do people seem to either love it or hate it?

There is a genetic component to cilantro taste perception. A mutation located within a cluster of olfactory receptor genes was found to be significantly associated with soapy-taste detection. Among them is OR6A2 (Olfactory receptor 6A2), an olfactory receptor (see Figure 9) with a high binding specificity for several of the aldehydes that give cilantro its characteristic odour. However, the authors of this study observed low heritability [27].

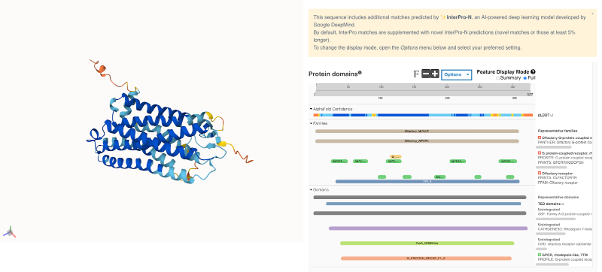

Figure 9. Split full-screen view of the (AlphaFold-predicted structure of the human OR6A2 receptor). The structure of this protein hasn’t been experimentally solved yet.

Figure 9. Split full-screen view of the (AlphaFold-predicted structure of the human OR6A2 receptor). The structure of this protein hasn’t been experimentally solved yet.

At least five other different receptor variations have been associated with the differences in the perception of coriander [28, 29]:

- OR4N5 (Olfactory receptor 4N5)

- TAS2R1 (Taste receptor type 2 member 1), which is probably related to the perception of bitterness.

- TRPA1, the Wasabi receptor, which activates in response to a high variety of compounds (see above Figure 7).

- GNAT3 (Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(t) subunit alpha-3, or Gustducin alpha-3 chain), a signalling component for taste, is common to bitter, umami and sweet perception [30, 31].

- TAS2R50 (Taste receptor type 2 member 50), a taste receptor that plays a role in the perception of bitter flavours.

Besides, it’s important to note that the soapy taste issue is specific to the leaves (coriander, or cilantro in U.S. English). The seeds (coriander spice or coriander seeds) have a different flavour profile and usually do not trigger the same aversion.

However, genetics is not the only factor. Cultural exposure and personal food experiences also play a role [28]. People who grow up in regions or families where coriander is commonly used are more likely to enjoy its flavour. Conversely, those who aren’t exposed to it early or often may find its taste overwhelming or unpleasant when they first try it.

Is there any example of variations in a single protein influencing taste?

The TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor (Taste receptor type 2 member 38, see Figure 10) is responsible for the ability to detect the compounds phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) and propylthiouracil (PROP). Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, turnip, collard greens and rutabaga have glucosinolates, compounds that are structurally similar to PTC. It has been suggested that individuals who perceive glucosinolates as strongly bitter may find cruciferous vegetables to be very bitter [32].

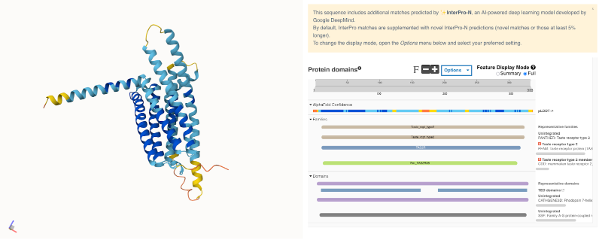

Figure 10. Split full-screen view of the (AlphaFold-predicted structure of the human TAS2R38 receptor). The structure of this protein hasn’t been experimentally solved yet.

Figure 10. Split full-screen view of the (AlphaFold-predicted structure of the human TAS2R38 receptor). The structure of this protein hasn’t been experimentally solved yet.

Nevertheless, there are other factors influencing taste in this case as well [33].

Besides, TAS2R38 has been associated with the molecular physiological mechanisms implied in the biological process of ageing [34], and the perception of PTC/PROP has also been related to health conditions including colonic neoplasm risk [35] and even neurodegenerative diseases [36].

References

[1] PMID: 21036327

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/taste-receptor

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/taste-receptor

[4] PMID: 28655883

[6] PMID: 31922012

[7] PMID: 22110046

[8] PMID: 17115053

[9] PMID: 39468215

[10] PMID: 27322240

[11] PMID: 21315593

[12] PMID: 14712238

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pungency

[14] PMID: 27367653

[15] PMID: 24305160

[16] PMID: 19074743

[17] PMID: 11473305

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capsaicin

[19] PMID: 18695236

[20] PMID: 30001322

[21] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389041720300772

[22] PMID: 40314109

[23] https://bigthink.com/life/why-people-like-spicy-foods/

[24] PMID: 23538555

[25] PMID: 37686747

[26] PMID: 35164163

[27] https://flavourjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2044-7248-1-22

[28] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/cilantro

[29] PMID: 22977065

[30] PMID: 38600377

[31] PMID: 38776963

[33] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950329313001572

[34] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-54604-1

[35] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020464