Interpro7 a not So Formal technical view

interproOn September 25th 2019 the traffic manager system at EBI underwent a small change: the URL https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/ now redirects to a different machine. And just like that, the project we had been working on for over 3 years became the official InterPro website.

I was very proud: https://twitter.com/4ndr01d3/status/1176864755384037376

I know what you are thinking: 3 years!! To build a website? 3 years! Yes, that long, but in my defence it wasn’t just a Look & Feel change (although, I’m also proud of the new look). Instead the InterPro website went through a complete re-factor: we created an API that our users can query to get InterPro data programmatically. The website uses that API to get the content of every page. The website is responsive, and can even be added to the list of apps in your mobile.

So, if you are interested in the technical details of all these changes, please keep reading, otherwise, just enjoy the new website:

- Go to your favourite protein

- Check the domains that have matches in it

- See if there is a PDB structure and were those domains are actually located

- Look for similar proteins

- Go to Browse and start filtering the data and find something you are interested in

And let as know, send us an email to interhelp@ebi.ac.uk with your opinions and ideas, we are very keen to hear what you think about the new InterPro.

Are you still reading? Damn, I guess I need to actually talk about the technical stuff. So here is the plan: I’m going to write two posts, one about the API and the other about the website, as they are literally 2 independent github projects: https://github.com/ProteinsWebTeam/interpro7-api and https://github.com/ProteinsWebTeam/interpro7-client.

Application Program Interface [API]

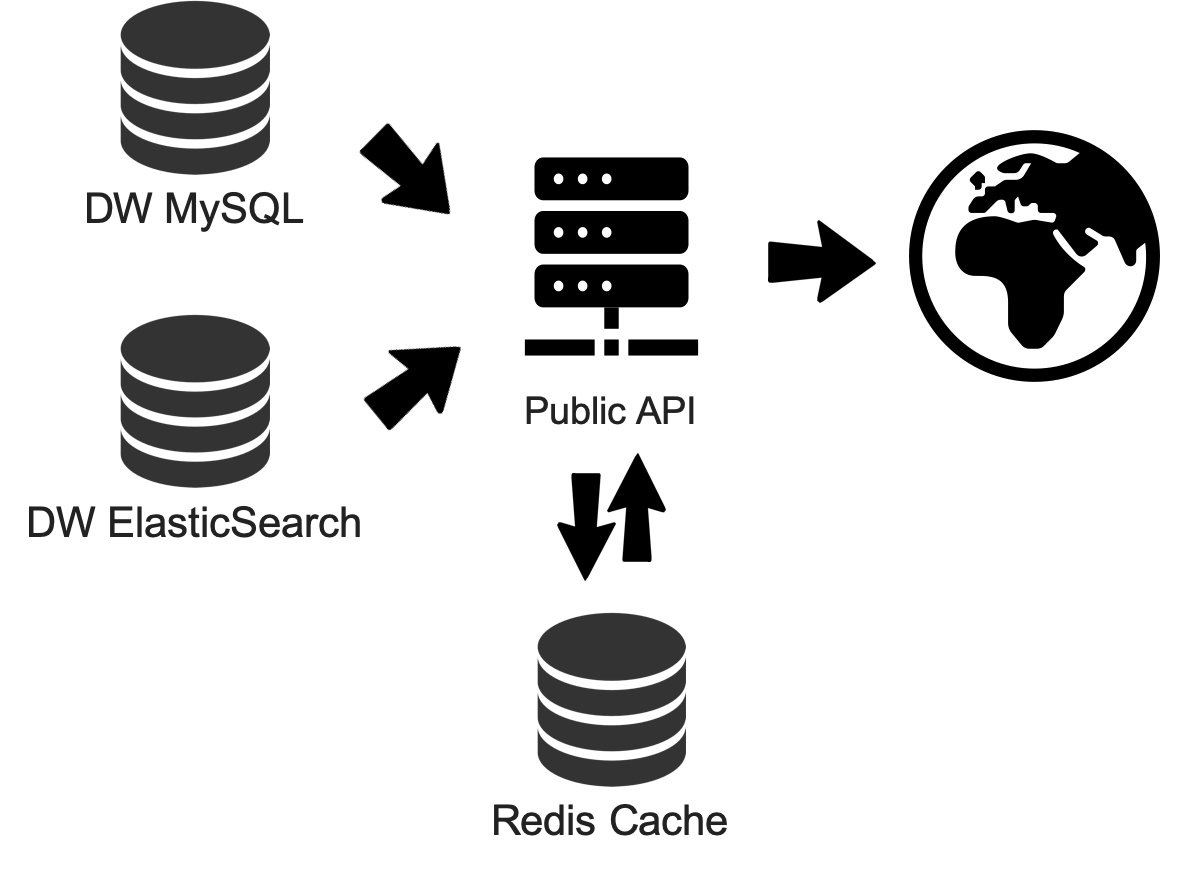

The InterPro API follows the REST approach, and is read-only; so basically we only implemented the GET method. In a nutshell, the user sends a URL and the API returns a payload. The API is accessible through this URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/api/ and has 6 endpoints: entry, protein, structure, taxonomy, proteome and set. For each endpoint the user can request:

- An overview reporting how many entities of that type exist. For example the payload of /protein tells how many proteins are in the DB, and how many of those are curated.

- The list of entities of the selected endpoint. For example /entry/interpro provides the list of Interpro entries.

- The details of a particular entry. For instance /structure/pdb/1b2v includes information about the 1b2v structure: its name, description, resolution of the experiment, etc.

- The endpoints can be mixed to filter the information. For instance /protein/reviewed/entry/interpro/structure shows the reviewed proteins that have matches with an Interpro entry and also have experimental structures.

So let’s talk about the technologies we have chosen. The API is implemented in Python 3, it uses Django and the Django Rest Framework. It uses GUnicorn and Apache for production. Its data store combines MySQL and Elasticsearch.

We think that using an existing and recognised framework not only saves you from rewriting tons of code, but also defines certain constraints to the developer team, and forces the team to produce code that team members will hopefully be familiar with. The DRF extends the Django project to simplify the process to go from a URL to the payload.

On the most basic level, the way we use DRM is to create views for each of the parts of a URL, and each view filters the data store. Once the subset is defined, it uses a serializer to create the payload in a given format, which usually is JSON. If for example, the API receives the request /entry/pfam, the /entry view defines that the data store is seen from the point of view of entries, then the /pfam view filters the entries to only the ones coming from the member DB pfam. Eventually, this dataset reaches a serializer that creates a JSON with the first 20 entries, which is the default page size.

When querying a single endpoint as in the example above, the API only queries our MySQL instance because all the information is contained in a single table, so it is expected to return the results quickly. However, when more than 1 endpoint are combined, MySQL would be too slow; remember the API should cope with the needs of a modern website.

Take into account that at the time of writing, the number of proteins in the Uniprot DB is just over 190 million. And therefore a JOIN with such a table can easily create temporary tables of up to billions of records.

Our solution to this was to precalculate all these combinations and store them in a single denormalized index in elasticsearch; it currently has 1.8 billion documents. This however is not a perfect solution because now the API spends most of its time aggregating queries to be able to get unique values. But now, those queries can be solved in the order of minutes, while with just using MySQL, they would have taken hours, or days in some cases.

Wait a minute, did I just say minutes? How is it that an API that serves a website can take minutes to answer a request? What user is going to wait several minutes for a page to load? And the answer to these and other questions is caching… A LOT of caching.

API Caching strategy

We do heavy caching of our data, in both the client and the API. Here we will only cover the API side of things. Both MySQL and elasticsearch have their own cache. But we quickly found out that these native features were not enough for our requirements. Their strategy is based on when the last time was that a query was executed. However, there are queries that we would like to have ready, even if they haven’t been executed for several days. I guess there might be ways to have control over this in elastic, however this would imply having more atomic control, and therefore the complexity of our API would grow more than what we would like to. We decided to include another layer of caching using Redis in our production machines. Here is how it works:

- Before an InterPro version release gets published, we preload the queries that we have identified to be necessary for the website into Redis, for example, to apply the different filters in the Browse section, or the queries required for the homepage.

- Once the new data release is out, and a user visits a page that requires something new, this query gets executed and if it takes less than a minute, the payload is returned and saved in the cache for any future requests.

- If the query takes more than a minute, a time-out response is given; but the query keeps running in the background, and whenever it gets a response, the payload is cached. When the page tries again to access this data, the response would be almost immediate because it would be coming from the cache.

Deployment in production

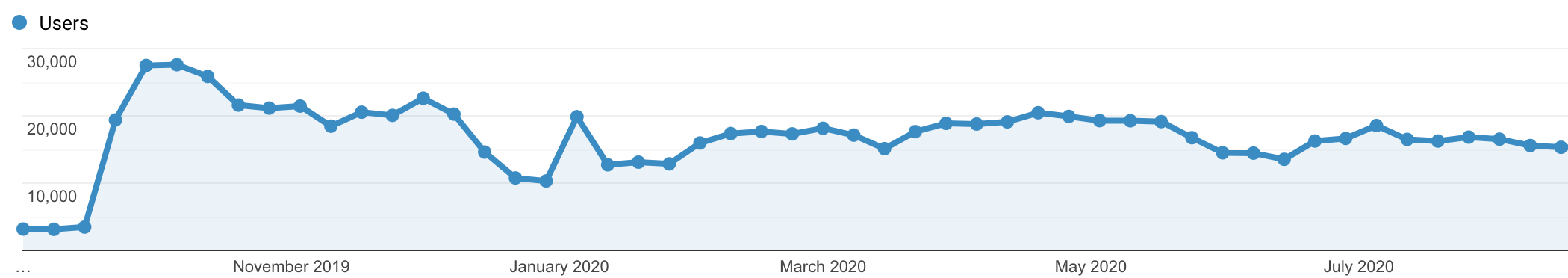

The InterPro website is on average serving around 1800 users per day, but that includes weekends. On weekdays, we usually have around 2700 users, but there are days that it can go to around 4500; The highest during January 2020 was 4572 on the 6th of Jan - I guess everyone was eager to do their analysis after the holidays.

The graphic below shows how many users per week have used the InterPro website From September 2019 to August 2020.

I’m showing you these numbers so you know that although we are not in the major league, we have a significant number of users, and therefore our production setup requires some thought. Currently, this is what we have:

- 3 Internet facing machines, one to serve programmatic queries and 2 to serve the website. Each machine uses apache to deal with the traffic and serve the static files. Apache connects with GUnicorn by an HTTP socket, and gunicorn is the one running our app.

- There is a common Redis installation for these machines so they all share the same cache.

- We have a small cluster (3 machines) serving elasticsearch, splitting the data in 1 shard per member database, and having 1 replicate running on the same machines.

- 1 MySQL instance.

This whole setup is replicated in our failover cluster, so if something goes wrong with the live cluster there is a backup.

Of course, we would like to have more machines in this setup: more for the elasticsearch cluster, so queries can run faster, and more facing machines, so we can serve more users, but resources are limited and for now that’s what we have.

Coming soon…

I’ll be writing a similar post about the website. Spoiler alert: expect React, Redux, Web components, webpack.