Technical View Of The Interpro Client

interproIn the last post we discussed the technical details of our API. We talked about how the website influenced some of the performance requirements of the API. The website, or for that matter any other client, was seen as a black box that created requests that the API needed to respond to. In this article we will switch those roles and delve into technical details of the web client, whilst treating the API as a black box that always responds to the client’s requests.

Starting with the basics, the InterPro web client is a Single Page Application (SPA), this means that if you visit the home page in your browser, it executes a normal web transaction: it fetches the html file from our servers, the browser reads that file, renders the web page, and determines which other files are required: JavaScript, CSS, favicon, images, etc. The difference in SPA is that when the JavaScript (JS) is executed, it intercepts the logic in the browser to follow links and replace it with its own logic. So, if the user clicks on a link, the browser doesn’t start a new web transaction, instead, the JS logic manipulates the current view of the page to reflect only the changes required by a given user interaction.

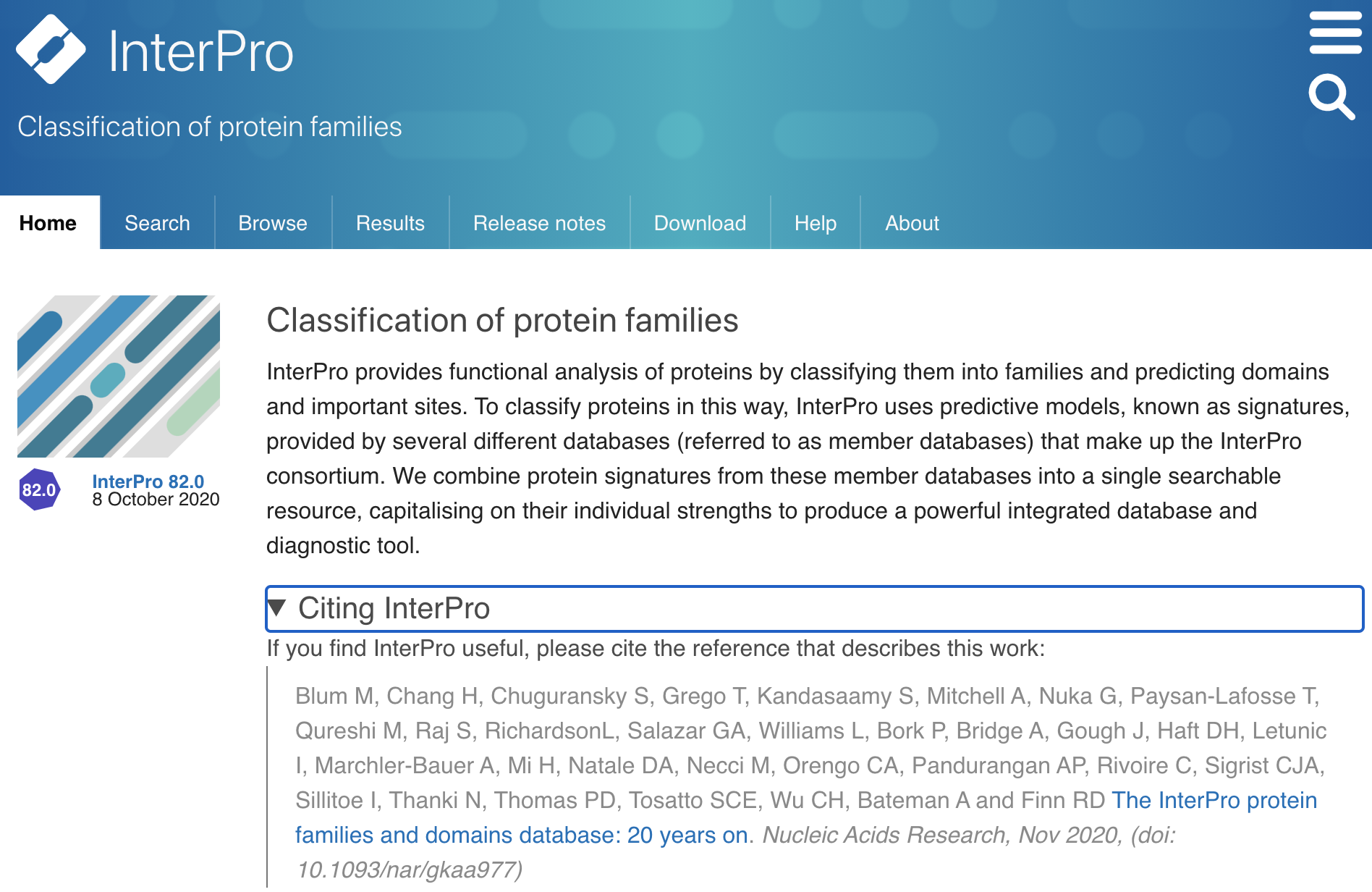

The main advantage of a SPA is that the webpage doesn’t need to be rendered completely every time a user clicks a link: it just updates the part of the page that is required. For example, if you visit our home page and click the Citing InterPro link, the information gets displayed under that link and the rest of the page stays the same, no need for redrawing the banner, menus, or any other parts of the page, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Citing InterPro information on InterPro home page.

Figure 1. Citing InterPro information on InterPro home page.

That example is not showing anything new, asynchronous JS has been around since the early 2000’s and tinkering pieces of a webpage, or more formally talking, DOM manipulation is basically the reason why JavaScript exists. But building a SPA means complete immersion on that idea, the whole website is created that way and with it comes a problem of scale: If all your website is now dynamically generated in JS, how do you organise your code? and your assets? how to optimize changes in the DOM? Enter React.

InterPro client is a React App

React is not the only framework that attempts to answer those questions. There are other widely used frameworks in the web development world, for example Angular and Vue. Without going into details of each framework, we took the decision of developing with React about 5 years ago and we are still happy with it. Back then, Vue wasn’t mature enough as a technology and AngularJS was being rewritten to what is today called Angular.

Anyway, we started playing with React for demos and prototypes of the website. Organising our code into visual components, made sense, and writing JSX (React language to write components) was simple enough, so it slowly started to take shape and those initial prototypes evolved in what you can see now as our live website.

React organises an app as a set of visual components. Taking a simple example from InterPro, the Loading component, which is basically 3 dots that are animated to inform the user that part of the page is still loading. This component is defined once and we can use it wherever we need it. We use the Loading component over 50 times in our code, it is probably the most popular of our components. If one day we decide to change that animation for something else, we would only need to change 1 file and the change will be reflected in all those 50 instances.

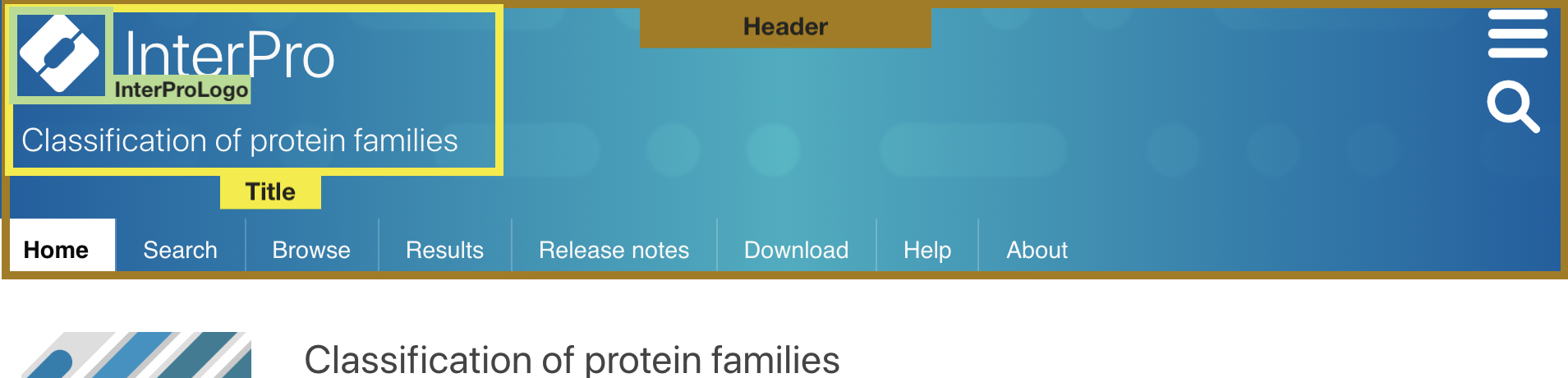

You can then use React components to create other components, so for example when you are at the home page, we are displaying the Header component, which contains the Title component, which in turn contains the InterProLogo component, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. InterPro header components organisation.

Figure 2. InterPro header components organisation.

One thing React does very well is to limit updates to parts of the page that have changed, so if a user clicks on the Search button, all the components under the menu will change, but the menu and header will remain the same. React makes sure that the changes in the page are as efficient as possible, avoiding unnecessary renderings. It uses a technique called Virtual DOM.

Sharing info among components (Redux)

Splitting your application into small components helps to abstract the functionality of each part of your website, so you can focus on one particular thing at a time. Data in a React component can be classified into 2 types:

- Props: External values that are sent to the component. You can think of them as the parameters of a function, or the attributes of an html element.

- State: Internal values that the component uses to keep track of things that are relevant for its behaviour. For example, a push button needs to remember if it has been pushed or released. That info is internal to that component, therefore it goes in its state.

React defines a strategy on how to share data among components, which works by sending data to child components via its props, and lifting the state into the parent component so a child can communicate with it. This child <=> parent communication strategy works well when you are dealing with a few components, but as you can Imagine a SPA can have hundreds of components. The InterPro home page, for example, can easily have more than 500 components (e.g. the Link component appears over a hundred times in it).

So in order to share information among so many components we use Redux, you can think of this library as a global state, where all the components of your app can read data from and also put new data there by dispatching an action, with the advantage that every component that is ‘connected’ to the redux state, gets notified when the data they are reading changes. To be honest, the learning curve for redux seemed a bit steep to me, there are several new concepts that are necessary to get a good handle on it. I can now understand why it was done that way, and what are its benefits, it actually seems simple now, but I guess it’s always like that with new stuff.

OK so back to InterPro, what do we keep in this global state?

- A logical representation of the current URL/location.

- The current values of the website settings.

- The current status of the API we use: InterPro API, EBI Search, Genome3D, etc.

- Download jobs

- InterProScan jobs

- Favourite entries

Thanks to this, for instance, a user choice to see tables with 50 results per page is applied all around the website, from the browse area to the list of proteins that have matches with an InterPro entry.

But by far, the task that uses Redux the most in our website is the handling of the URL and its mapping into a data structure in the global state. Remember I said earlier that a SPA replaces the default logic in the browser to deal with links; so this is our take on it:

- We have a data structure in the Redux state that represents a location in our website.

- When the user clicks on a link that goes into another part of the InterPro website, the Redux state gets updated with the new location.

- Any component that reads the location from Redux gets notified and acts accordingly, some components appear, some disappear, some get updated and others stay the same.

- The data structure gets mapped into a string URL that is then pushed into the browser history stack.

- Any change in the browser history (e.g. using the back button, editing the URL in the bar), forces an update in the Redux location data structure, and then again components get updated.

Figure 3. Cascade of events happening when a user clicks on a link pointing to a different page in InterPro. (1) In the initial step of this scenario, the app is already in the page /entry/InterPro/ and the redux states represent that location as shown on the table. (2) The user clicks on IPR000001. (3) The new logic for internal links updates the redux state. This triggers a series of events, including (4) updating the URL using the browser history API, and (5) updating all the components that read the location from the state.

Figure 3. Cascade of events happening when a user clicks on a link pointing to a different page in InterPro. (1) In the initial step of this scenario, the app is already in the page /entry/InterPro/ and the redux states represent that location as shown on the table. (2) The user clicks on IPR000001. (3) The new logic for internal links updates the redux state. This triggers a series of events, including (4) updating the URL using the browser history API, and (5) updating all the components that read the location from the state.

Loading data and client cache

One important missing piece at explaining the InterPro client is how we get the data from the API. For this we created what in React is called a Higher-Order component. Which is basically a wrapper component that adds some logic to the wrapped component. Redux uses the same technique when we connect a component into the global state.

The higher-order component that we created is called loadData. It receives getUrl as one of its parameters,and has all the logic to fetch the data of that URL, transforming it into a data structure and including it as a prop of the wrapped component.

For example, in the Browse page we have a series of filters, one of them, filters by the type of entry, to be able to have only the families, domain, etc. This filter needs to get data from the API to be able to know how many entries per type are in the database for the current selection.

To do this the getUrl of the loadData that wraps the EntryTypeFilter is a function that creates the API URL taking into consideration the current combination of the other filters. Then loadData loads the data, duh, and puts it in the props of the component. The component is agnostic of how that data got there, but it can use the data to create the radio buttons.

One more thing that happens in loadData is that once we get a response, it is saved in the Session Storage of the browser, and any subsequent requests for that exact data will be responded with the already obtained data, so it doesn’t have to fetch data again from our API. We keep track of the InterPro data version, so this cache gets discarded when we detect there is a newer release.

Release and deployment

Although there are many details I can go from here I think this post got long enough and to be honest I doubt many people got this far into the text, but if you did, the last thing I want to mention is our release and deployment strategy. The tool we use for bundling and optimizing the final release is webpack. There are quite a few things that happen at that stage, sometimes webpack does the job, sometimes it orchestrates other libraries to get it done.

The basic task of a bundler is to merge all those javascript files we have in development and create a single file that includes only the things we actually used. But it goes beyond that, and in combination with babel the code gets transpiled into code that is understood for most browsers, our current rule is to cover browser versions that have at least 0.25% popularity in the global usage statistics.

The code is also minimized, and we actually set it up to get compressed at this stage in both gzip and brotli, so that it takes the minimum space possible for the transfer between the web server and the browser.

But then, you ask, if you create a single bundle with all the JS files used, and what you created is a SPA, aren’t you sending the whole App at once, even if the user only opens a single page and never navigates anywhere else?

Glad you ask, on the one hand, that doesn’t include the actual data, as you remember from the loadData section; on the other hand, we use a method called code splitting, in which you make use of dynamic imports to let the bundler know where is a good place to split the code. Webpack then creates several parts of the bundle and the main bundled file includes logic to dynamically get the other parts when they are required.

Conclusions

And that’s it. We end up covering a lot of technologies and methods that we used for developing the new InterPro website. That, of course wasn’t a complete list of all the things we used, but if you are interested in web development, it should have given you a clear idea of what we have done in this project.

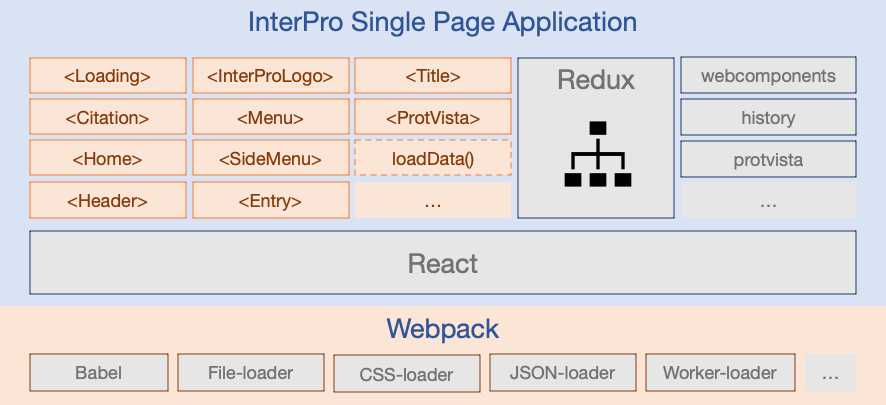

Figure 4. Summary of the InterPro website components. The top area represents the components (orange) and libraries (grey) that are included in the InterPro SPA, making a special emphasis for React and Redux, as they are the fundamental dependencies of the system. In the bottom area are the webpack, which is the orchestrator of the release and deployment procedures, and some of the libraries used for that purpose.

Figure 4. Summary of the InterPro website components. The top area represents the components (orange) and libraries (grey) that are included in the InterPro SPA, making a special emphasis for React and Redux, as they are the fundamental dependencies of the system. In the bottom area are the webpack, which is the orchestrator of the release and deployment procedures, and some of the libraries used for that purpose.

The InterPro client is an open source project and you can get the code in github. If you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us via interhelp@ebi.ac.uk or via twitter @InterProDB and I’ll be happy to talk more tech stuff.