Interpro And Intrinsically Disorder Proteins

focusStructure is more conserved than sequence

As Linus Pauling, a double Nobel laureate (Peace 1962 and Chemistry 1954), stated, “If we want to understand cells, we must know their structure in terms of molecules” [1]. With this purpose in mind, to grasp the physiology of living organisms, we study proteins at the molecular level. To illuminate our path, we rely on the potent light shed by the evolutionary process, as nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution [2].

Throughout the billions of years in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, protein structures have been better preserved than their amino acid sequences [3, 4]. Therefore, the identification of distant evolutionary relationships between proteins is considerably more effective when comparing structures rather than when comparing their sequences [5, 6, 7]. In fact, due to the recent surge in high-quality structural predictions, the identification of new protein domains and the precise determination of their boundaries have been accelerated through the millions of structural models generated by artificial intelligence techniques [8, 9, 10, 11].

Challenges in analysing disordered proteins and tools for assessment in InterPro

There are instances when protein structures, which are ultimately responsible for the protein functionality, present challenges in their analysis, prediction, or experimental characterisation. A significant proportion of proteins or protein regions exist in a disordered state when considered in isolation, which accounts for approximately one-third of the human proteome [12]. This disordered state can appear as either a lack of a stable structure throughout the entire sequence or as specific regions within the protein, known as intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), respectively [13]. In these proteins, comparing the structural form of their monomeric state with other proteins does not enable us to identify structural similarities that would allow us to infer homology.

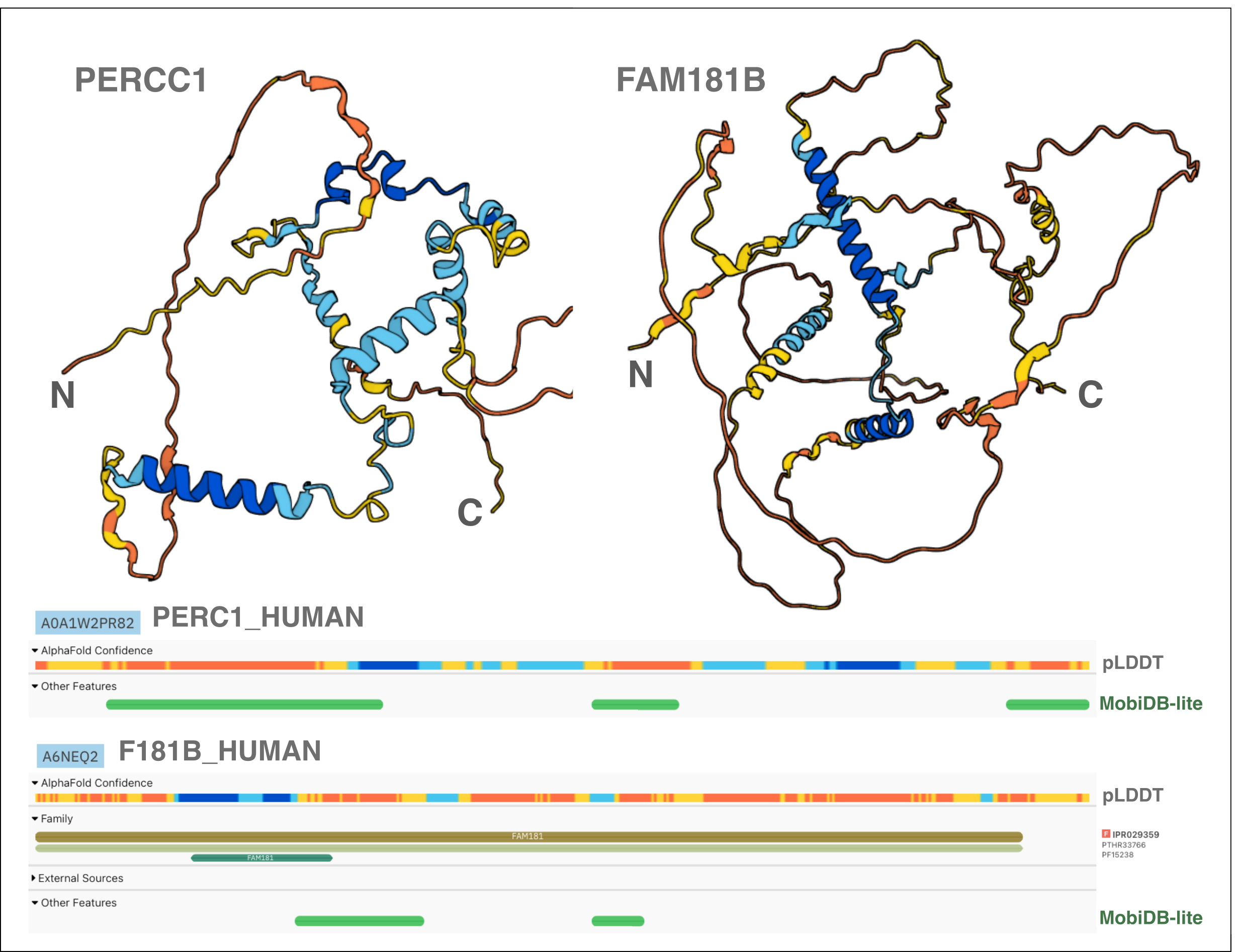

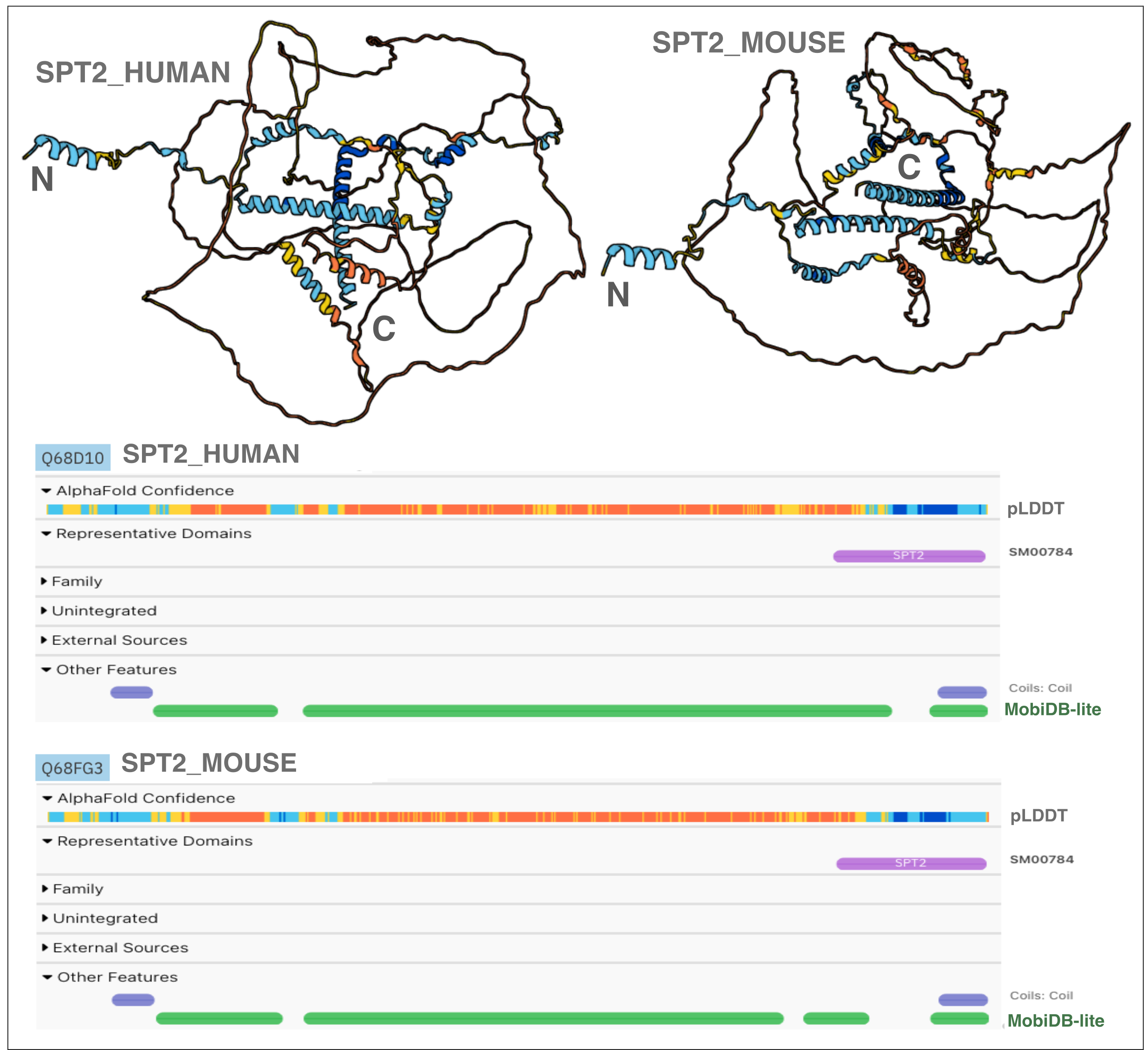

Using InterPro, we can easily determine whether our protein of interest is an IDP or rich in IDRs [14]. Recently, the DisProt database, a major manually curated repository of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins [15], has been integrated into InterPro. Additionally, in InterPro, we can map the output of MobiDB-lite (a consensus disorder prediction tool) [16] and the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) confidence scores from AlphaFold [17], these scores provide information about structural stability at the residue level, with a pLDDT value below 70 indicating potential lack of stable structure in isolation (cartoons coloured in yellow and red in Figures 1 and 3).

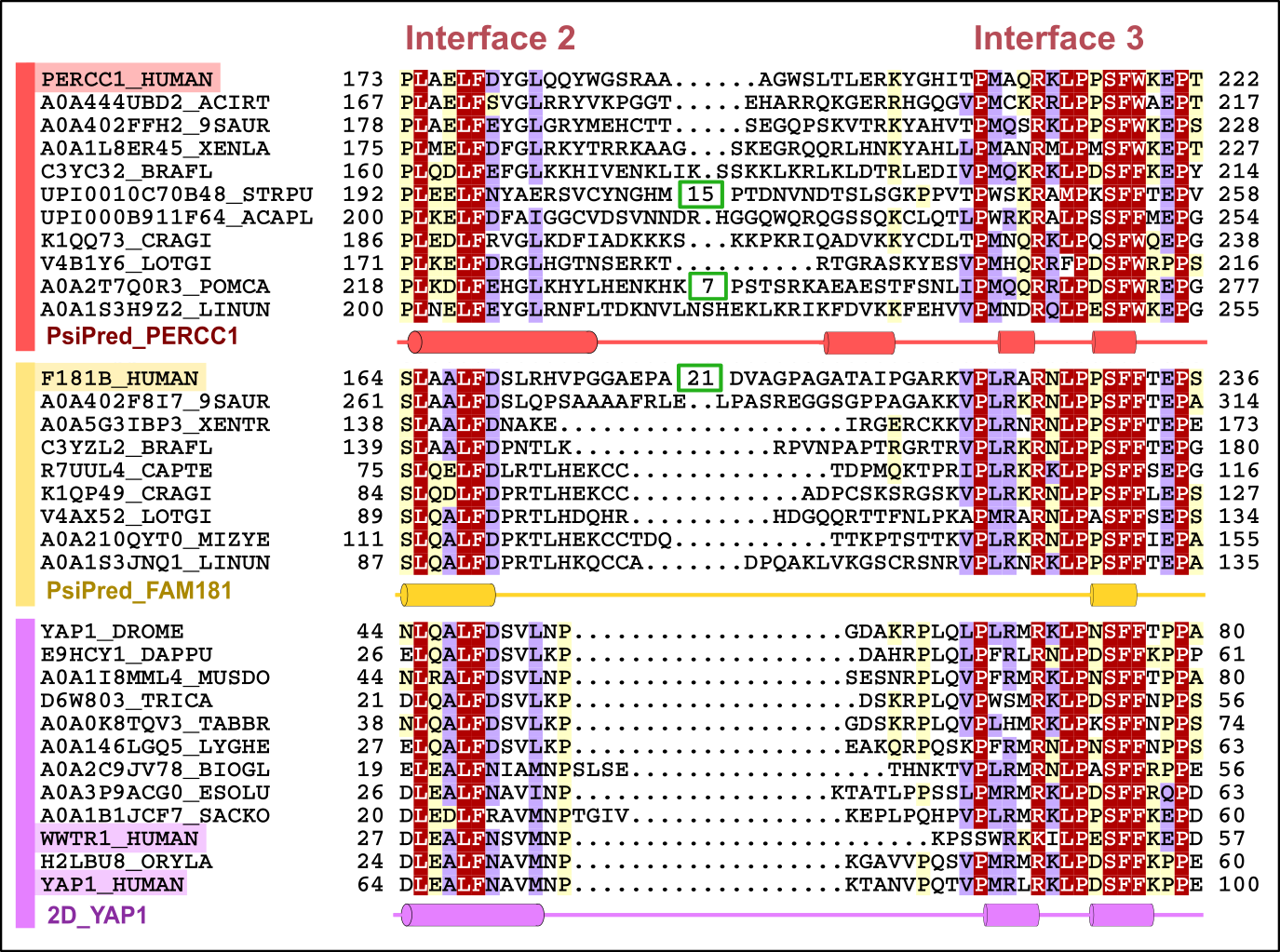

An example of such proteins, rich in IDRs, can be found in the Yap/Taz/FAM181/PERCC1 family in humans (Figure 1). Several members of this family have been experimentally described as regulators of transcriptional activity by interacting with TEAD (TEA/ATTS domain) transcription factors, which serve as the main nuclear effectors of the Hippo pathway, crucial in regulating organ size and maintaining tissue homeostasis in animals. The structural similarity among Yap/Taz/FAM181/PERCC1 family members becomes evident only when we examine these structures while they interact with the proteins they specifically bind to, the TEAD transcription factors. However, their recognition as homologues was only achievable through the identification of conserved regions in their amino acid sequences, using classical computational tools for identifying statistically significant sequence similarity based on the comparison of profiles against sequences (HMMER) and profiles against profiles (HHpred) (Figure 2) [18].

Figure 1. AlphaFold predicted structure and protein sequence viewer of the AlphaFold pLDDT score and MobiDB-lite prediction for PERCC1 and FAM181B. The figure displays the AlphaFold models (cartoons coloured by pLDDT confidence score) and the MobiDB-lite predictions in the protein sequence viewer as displayed on the InterPro website for two human paralogues (PERCC1 and FAM181B proteins) rich in IDRs.

Figure 2. Representative multiple sequence alignment of two consecutive TEAD interaction motifs (‘interfaces 2 and 3’) in Yap/Taz/FAM181/PERCC1 family. Protein subfamilies are indicated by coloured bars at the left of the alignment: PERCC1, FAM181B and YAP/TAZ are indicated in red, yellow and purple, respectively. Limits of protein sequences included in the alignment are indicated by flanking residue positions. Numbers inside green boxes represent excised unconserved sequence. The alignment was generated with T-Coffee and presented with the program Belvu using a colouring scheme indicating the average BLOSUM62 scores (which are correlated with amino acid conservation) of each alignment column: red (>3), violet (between 3 and 0.8) and light yellow (between 0.8 and 0.2). Sequences are named according to their UniProt identification.

Another example is the family of histone chaperones SPT2, which is widely distributed among eukaryotes. Their conserved regions correspond to randomly distributed α-helices (Figure 3), and their homology is impossible to deduce through the comparison of their structures (see video at: https://youtu.be/WqaDEgl4VeY). In this case, only sequence conservation analysis enables us to establish orthology relationships and define this family [19].

Figure 3. AlphaFold predicted structure and protein sequence viewer of the AlphaFold pLDDT score and MobiDB-lite prediction for humans and mouse SPT2. The figure displays the AlphaFold models (cartoons coloured by pLDDT confidence score) and the annotations found in InterPro for two SPT2 orthologues (human and mouse SPT2 proteins) rich in IDRs.

To bring order to disorder… protein sequence conservation

Despite having a wealth of high-quality protein structural data, both experimental (PDBe) and computationally predicted, such as those produced by AlphaFold and Meta AI-ESM Metagenomic Atlas [17, 20, 21], in the case of IDPs and IDRs, we won’t be able to establish homology relationships through the comparison of their known or predicted monomeric structures.

To shed light on this “Dark Proteome”, the identification of protein sequence conservation will continue to be essential for understanding, classifying, and deciphering IDRs roles. The databases of sequence conservation-based protein alignments, such as Pfam, Smart, or CDD, integrated into InterPro, play a pivotal role and will continue to be highly valuable tools in the task of predicting protein functions for proteins rich in IDRs.

InterPro provides a comprehensive view, facilitating the identification of protein regions where disorder and evolutionary conservation overlap - areas that, despite their predicted unstable structure, likely hold significant functional relevance [22].

References:

-

Linus Pauling Lecture: Valence and Molecular Structure, Oregon State University (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tevU4Cu4XE).

-

Dobzhansky, Theodosius (March 1973), “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution”, American Biology Teacher, 35 (3): 125–129, doi:10.2307/4444260, JSTOR 4444260, S2CID 207358177; reprinted in Zetterberg, J. Peter, ed. (1983), Evolution versus Creationism, Phoenix, Arizona: ORYX Press

-

Rost B. Twilight zone of protein sequence alignments. Protein Eng. 1999 Feb;12(2):85-94. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.2.85. PMID: 10195279

-

Chothia C and Lesk AM. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J. 1986 Apr;5(4):823-6. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04288.x. PMID: 3709526

-

van Kempen M et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat Biotechnol. 2023 May 8. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01773-0. Online ahead of print. PMID: 37156916

-

Holm L et al. DALI shines a light on remote homologs: One hundred discoveries. Protein Sci. 2023 Jan;32(1):e4519. doi: 10.1002/pro.4519. PMID: 36419248

-

Holm L. Dali server: structural unification of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jul 5;50(W1):W210-W215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac387. PMID: 35610055

-

Barrio-Hernandez I et al. Clustering predicted structures at the scale of the known protein universe. Nature. 2023 Oct;622(7983):637-645. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06510-w. Epub 2023 Sep 13. PMID: 37704730

-

Schaeffer RD et al. Classification of domains in predicted structures of the human proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023 Mar 21;120(12):e2214069120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214069120. Epub 2023 Mar 14. PMID: 36917664

-

Zhang J et al. DPAM: A domain parser for AlphaFold models. Protein Sci. 2023 Feb;32(2):e4548. doi: 10.1002/pro.4548. PMID: 36539305

-

Sanchez-Pulido L and Ponting CP. Extending the Horizon of Homology Detection with Coevolution-based Structure Prediction. J Mol Biol. 2021 Oct 1;433(20):167106. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167106. Epub 2021 Jun 15. PMID: 34139218

-

Bhowmick A et al. Finding Our Way in the Dark Proteome. J Am Chem Soc. 2016 Aug 10;138(31):9730-42. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06543. Epub 2016 Jul 19. PMID: 27387657

-

Moses D et al. Intrinsically disordered regions are poised to act as sensors of cellular chemistry. Trends Biochem Sci. 2023 Aug 30:S0968-0004(23)00204-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2023.08.001. Online ahead of print. PMID: 37657994

-

Paysan-Lafosse T et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D418-D427. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac993. PMID: 36350672

-

Quaglia F et al. DisProt in 2022: improved quality and accessibility of protein intrinsic disorder annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan 7;50(D1):D480-D487. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1082. PMID: 34850135

-

Piovesan D et al. MobiDB: 10 years of intrinsically disordered proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D438-D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1065. PMID: 36416266

-

Jumper J et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021 Aug;596(7873):583-589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. Epub 2021 Jul 15. PMID: 34265844

-

Sanchez-Pulido L et al. PERCC1, a new member of the Yap/TAZ/FAM181 transcriptional co-regulator family. Bioinform Adv. 2022 Feb 3;2(1):vbac008. doi: 10.1093/bioadv/vbac008. eCollection 2022. PMID: 36699391

-

Saredi G et al. The histone chaperone activity of SPT2 controls chromatin structure and function in Metazoa. bioRxiv 2023.02.16.528451; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.16.528451

-

Burley SK et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB.org): delivery of experimentally-determined PDB structures alongside one million computed structure models of proteins from artificial intelligence/machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D488-D508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1077. PMID: 36420884

-

Lin Z et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science. 2023 Mar 17;379(6637):1123-1130. doi: 10.1126/science.ade2574. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36927031

-

Holehouse AS and Kragelund BB. The molecular basis for cellular function of intrinsically disordered protein regions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023 Nov 13. doi: 10.1038/s41580-023-00673-0. PMID: 37957331